NFTs — A free market for memes

First-principle explainer of the paradigm shift that makes JPEGs expensive.

First-principle explainer of the paradigm shift that makes JPEGs expensive.

“Man is split in two,” wrote Ernest Becker in The Denial Of Death.

Humans are the only animal that can imagine the future. And so, imagine the future in which they are no longer alive.

To deal with its mortality, the mind creates an immortal story about itself: the ego. Man is split between a body destined to die and a mind that imagines living forever.

Imagination works through language.

We use language to build mental models of the messy world around us, and share them with others as stories. Storytelling networks individual minds into a collectively imagined reality, better known as culture.

Culture is what happens in-between minds: the inter-subjective. It operates from intimate to epic levels.

Intimate culture is what comes naturally between family and friends. At epic scale, culture replaces personal trust with grand stories we all believe in. Narratives like capitalism, democracy and Christianity, but also human rights, money and Nike. They have no grounds in the natural world, but are products of mind — crafted and shared through language — that become real as we collectively believe in them.

"You could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven." — Yuval Noah Harari

Imagining together is the mind’s triumph over bodily constraints. It mass-socialises us. No other animal can get millions of strangers to work together as a tribe.

While the first humans used imagination to outsmart prey and predators, our web of minds now programs the biosphere rather than vice-versa. Much like nature selects genes, culture selects ideas.

Ideas on what is good and bad program human behaviour through norms, values, religions and ideologies — encoded in laws and institutions.

Ideas on how to achieve more with less program the environment through technology — embodied in objects and structures.

Banks, courts, presidents, books, paintings, rubik’s cubes, cars, computers, and spaceships are language games made real.

The mind fantasises about life beyond the body. Fantasies network together into a new layer of reality: culture.

At first, the body drives the mind. Nature shapes culture. Over time, the axis shifts. Collective consciousness designs the world to fit its fantasy. New minds are born into the mind-made world and keep the daydream going.

The fantasy is real. It just doesn't start out as matter and atoms — but as perceptions, images, memories, puns, points of view, ideas, stories and hope. First private, then intimate, then public, eventually epic.

"In individuals, insanity is rare. In groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule." — Friedrich Nietzsche

Philosopher Ken Wilber maps reality as follows:

Language games, ideas or concepts take root in collective consciousness through:

Utility, at its core, is about survival. We use stories to make sense of nature’s overwhelming complexity. Stories are never literally true, but true enough to be practical and replicable.

The idea of God, for example, came about by itself in many places at many times in history. Not because it’s clearly true, but because it plausibly calms existential uncertainty in a scalable manner. Religion authenticates the mind’s will to eternity, promises ultimate justice and kickstarts community.

From a utility perspective, the god meme makes sense.

Utility leans into replicability: how easy a language game jumps from brain to brain.

Successful ideas resonate with the ego to parasitise the brain, turning it into a multiplication machine. Gods live on through words, art and music.

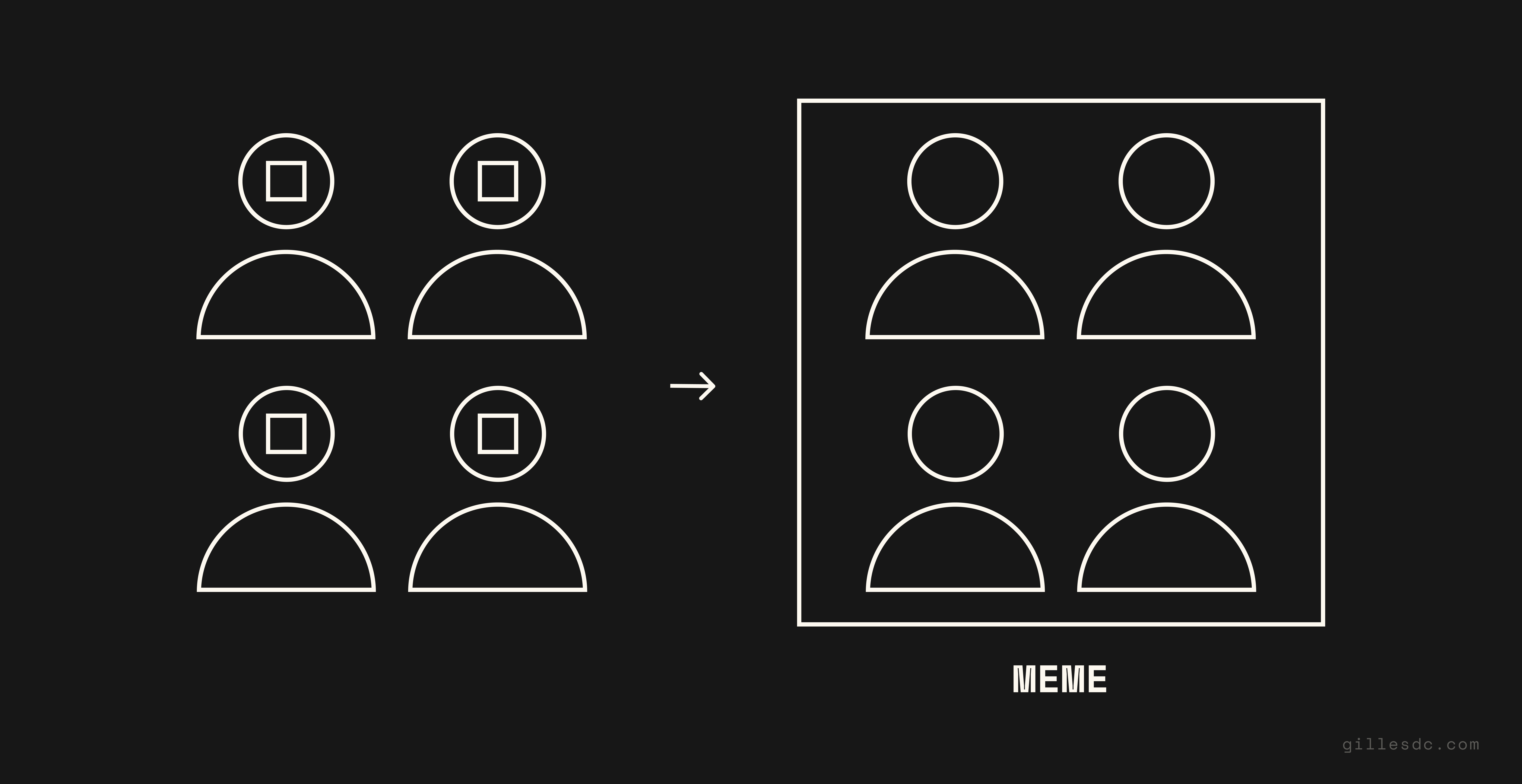

Humans are imitative creatures. We naturally mirror the ideas that inhabit our minds through language and art. Not necessarily because we like the idea — we also share out of hate and other emotions— but because we want others to know what we think of it. It’s how we signal identity: the individual ego asserts itself in collective culture by engaging with ideas in the inter-subjective. The idea, meanwhile, gains sway over an increasing number of minds with every mimic or share.

Reflexive idea sharing is known as “mimesis”. From mimesis, Richard Dawkins coined “meme” as the word for a self-replicating language game. Meme means “unit of cultural transmission”. Genes multiply nature through bodies, memes multiply culture through minds.

Eventually, the meme becomes established in behavior and environment.

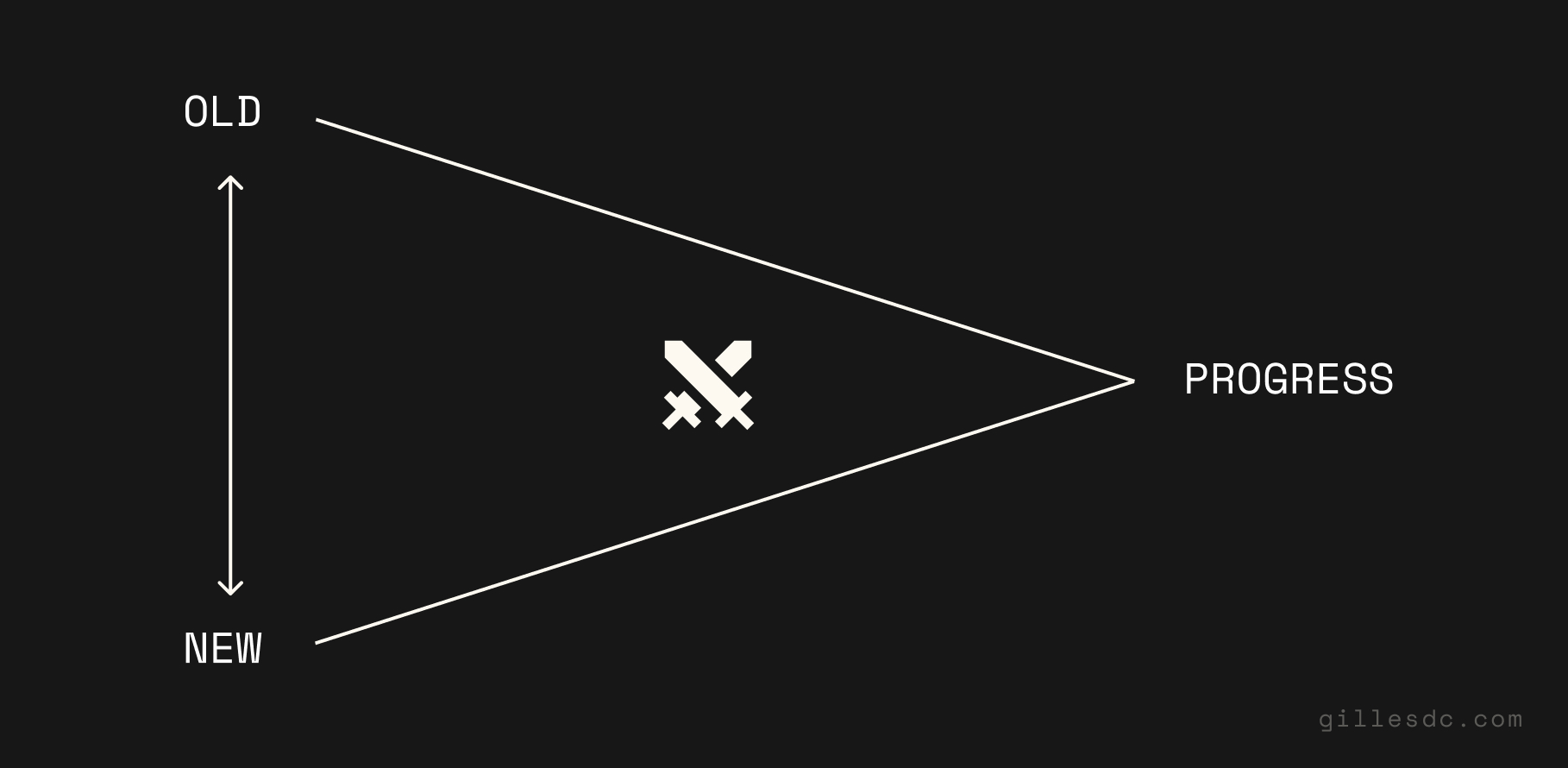

Establishment defends traditional (old) memes, even when they lose utility. To overcome traditions, progressive (new) memes need to win over minds with utility and replicability.

The god meme, for example, has long been retired by secular societies as grand narrative, but, to this day, lives on in buildings, rituals and institutions.

As I write this, the bitcoin meme (money backed by code) is challenging the established fiat meme (money backed by government).

Old ideas are proven. New ideas might work better, but carry risk: we don't know all unintended consequences. They must go through the mill of objection and scrutiny before they are to be adopted.

This cultural clash between habit and creativity drives human progress. Its trajectory across time is what we call history.

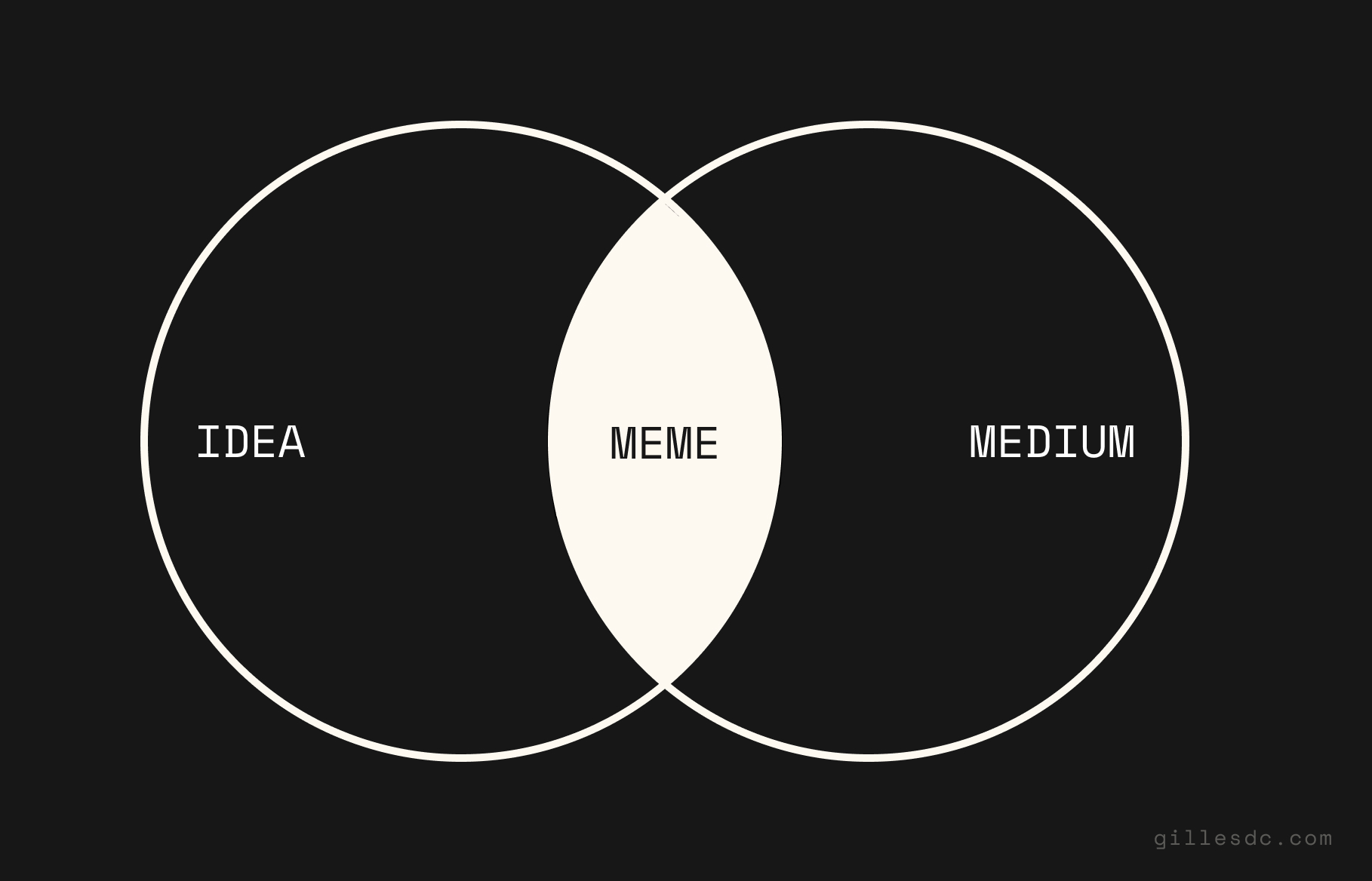

When I say meme, you think GIFs, annotated JPEGs and TikToks. Dawkins’ original examples were “tunes, catch-phrases, fashions, pot styles and building arches.”

The immaterial language game needs a material carrier to travel to other brains — via sound and sight.

Such idea carriers are known as media.

In a first-principle sense, a medium is a container that stores and broadcasts memes.

But there's more to media than meets the eye.

Essentially, all technologies and objects humans create are media: they store and project the memes that spawned them. The Chilean physicist César Hidalgo poetically speaks of crystals of imagination.

Because we construct and share imagination through language, language itself is the first medium downstream from the mind. Language makes the mind's magical world audible and visible to the ears and eyes of the neutral objective world.

"The world is but a canvas to our imagination." — Henry David Thoreau

Earlier, I said that memes multiply through minds.

You can say the mind is upstream of language, or equate language to the mind itself since it shapes thought. Whatever: the mind is the original medium.

The mind has ideas and broadcasts them through the body: in gestures, speech, writing, drawing, painting, sculpting, singing. Even facial expression, tone of voice, the way we walk. We're never not expressing the memes that make us.

All things we conventionally think of as media (books, podcasts, videos) store and broadcast ideas in a way our bodies can’t. That’s why we created them in the first place.

As per iconic media theorist Marshall McLuhan, “technology is an extension of the body.”

Technology augments what we can do. In doing so, it crystallises our collective imagination.

McLuhan is most famous for “the medium is the message.”

When we hear a tune or see a GIF, we don’t think of as an idea and its vehicle. It’s an undividable meme.

Book, car, pot, tweet or simply the words you use: a medium’s form and function define the meme to the point where they become one and the same. This plays out across multiple levels:

To thrive in the cultural environment, memes mutate across media to achieve maximum reproducibility.

Religious stories first spread slowly and scatteringly from mouth-to-mouth, then scaled uniformly through books that established rituals, values, traditions and institutions.

A meme is reproducible when it's easy to:

The stickiest memes are simple and visual. A picture, as they say, is worth a thousand words. Which is a more intuitive way of saying that brains process images ~16x faster than text. Showing beats telling.

Memes are LEGOs of culture: they click together to form new, more complex memes.

From the wheel are born chariots, bikes, cars, steering wheels, flywheels, wheels of fortune, spinning wheels, mills, pottery and more.

The wheel LEGO never needs to be re-invented, but can be re-used and re-mixed in ever-more complex configurations. Religion and ideology too network many LEGOs into complex narrative structures.

When memes dictate behavior, they create culture. When memes imagine better ways to get more with less, they create technology.

Remixing happens naturally and continuously through mimesis.

Every time you see or hear an idea and pass it on, you'll change it somewhat. You twist, turn and blend with other ideas you have in mind. Out comes a derivative of the input — itself derived from what came before.

By implication, ideas can never be entirely original.

The tweets you read today are far-flung, entangled mutations of mental models devised by the first humans. Perpetuated across time and space through minds of mimetic monkeys. Everything is a remix of a remix of a remix of a remix of a ...

Human civilisation accelerates because LEGO remixing compounds.

The more LEGOs (ideas), the bigger the surface area for new LEGOs (ideas) to integrate with. More LEGOs, more LEGO builders, more possibilities.

Creativity — that which leads to something "new" — is mixing what we already know in novel ways that somehow work. It's a team sport humans can play across seas and centuries, thanks to language-unlocked collective imagination.

“If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.” — Sir Isaac Newton

LEGO compounding shifts into higher gear when creativity invents new communication technologies. From speech to writing to printing to radio&tv to the Internet. With each invention, meme replication leaps by multiple orders of magnitude.

Memes invent technology. Technology scales memes.

Time to climb back up the rabbit hole.

By the time you read the tweet, you’ll barely think of it as a someone’s idea. You’ll think even less of all the preceding ideas that inspired it. All of which came to the tweeter through other tweets, videos, articles, conversations, education, language itself.

The tweet you read will inspire the tweet you’ll write — even if you’re unaware of it.

No offense, but you are a product of your mimetic environment.

Your mind is a screen onto which the memes around you project themselves. Those memes are, essentially, other minds, extended across space and time through bodies, objects, technologies — media. Your self-meme, also knows as your ego, interacts with these memes, and evolves in the process.

Every tweet you read executes a subliminal software update on your mind.

Man is a machine. Nothing enters our minds which is not directly or indirectly a response to stimuli beating upon our sense organs. — Nikola Tesla

We look outwards to make sense of a messy world, but in the process become inevitably conditioned by the memes we consume. Watch your meme diet.

Bringing it all together.

Next up is the metaverse: a completely virtual reality for people to socialise, work and play in. If that feels like a stretch, consider how much of our lives already happens in digitally designed realities.

The big point is that most of reality is made up, by memes that mutated through history.

The first memes were creations of the mind, but as new humans were born into existing cultures, the axis shifted. It's now the memes that make us.

Memes invent technology, build structures, allocate capital, rule markets, elect leaders, decide wars, distribute wealth, program how we behave and define how we see ourselves.

“People don't have ideas. Ideas have people.” — Carl Jung

“God is dead,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in The Gay Science.

To believe in something greater is a timeless human universal. For more than 2000 years, God had been our binding glue. By the time Nietzsche came around in the late 1800s however, we had antibiotics, electricity, engines, telephones and cameras. Not God but science had made the world smaller and less scary. Religion took a backseat to new grand narratives of infinite human progress. We had become gods ourselves.

Who killed God? The printing press.

Before press, people didn't read. Ideas were stored in manu-scripts — written by hand. Memes travel slowly because manual copying takes ages and one script can only have one reader at a time.

You get inverse network effects. On the demand side, why and how would you learn to read with so few books available? On the supply side, why would you dedicate months and years to writing with so few readers available?

Distribution of memes concentrates in the hands of the literate handful. In the European Middle Ages, this power fell to the Catholic Church. Monks in monastery libraries would spend their sweet time scouring, selecting and copying texts. Of course, only those lip-syncing the holy word made the cut. From there, it'd trickle down to the masses orally through church service, cathedral schools, and the first universities.

It was a case of systemic ignorance rather than outright censorship. People just didn't know any better. Non-religious texts were rare because nobody cared. Critical writing even less so because it'd get you killed. The word of God was truth itself.

In meme terms, the god meme monopolised mimesis in medieval society. People were born into it and lived life obeying, praying and repenting so they'd go to heaven after. Representing God's will on Earth, the Church was the only source of truth and culture. The sole meme dealer.

Introduced in by Johannes Gutenberg in ~1440, the printing press slashes the unit cost of text (meme) replication. Network effects flip. As books spring up like mushrooms, the common man learns to read, then write. Literacy and education grow to unprecedented levels.

Much to the Church's delight, at first. Bible sales were off the charts. But grapes quickly turn sour when critical readers discover glaring inconsistencies between God's word and the Church's actions. Corrupt practices like the sale of indulgences — you could pay for salvation — stir protest. Martin Luther and John Calvin openly challenge the Church, using mass print to rally masses to their opposing views.

There's a new meme dealer in town: Protestantism. Protestants and Catholics would be at each others' throats for centuries.

The religious clash is just the first stone of the multi-dimensional domino effect set in motion by the printing press.

In a nutshell:

Cheaper meme distribution shifts the power to shape culture from the hands of the one Church into those of the masses. In wake of Enlightenment, the decentralised meme pool would replace religion with ideologies like individualism, capitalism, liberalism, nationalism and democracy as the new cultural base layer: modernism.

The printing press demonstrates how technology and power counter-balance to guide culture.

Part I modelled how memes take center stage in culture when they're:

Culture progresses when new memes overcome established memes through utility and replicability.

So, was god killed by utility or replicability?

Humanist ideas (in earlier forms) had been around since the Greeks and Romans, but disappeared from intersubjective reality because replication technology (writing) was easily monopolised by the powerful, who pushed self-legitimising ideas instead.

The Church controlled meme replication until the printing press scaled replication to a scale that was economically impossible to contain. Competing memes popped up everywhere. God was printed out of relevance. Cultural order reconfigured, power redistributed.

Regardless of utility and replicability:

Humanist memes could only kill god with utility once technology broke the Church's power over replicability.

In a society:

With all the talk about culture, where does art fit in?

Part I proposed that all objects can be thought of as media that project ideas. A hammer broadcasts the concept of hammer. Thing is, that's not why hammers exist. They exists to hit nails. Hammers have objective value: same for everyone.

An object is art when its core function is to signal underlying ideas. Books, paintings, music, films, GIFs and TikToks express, contemplate, challenge, play with cultural values — often in attempt to transcend them. They exist to advertise ideas. Art objects have subjective value: different for everyone.

In other words, art objects are memes whose sole function is to be shared. They're products of self-expression, made real with skill so others feel amazed, understood, recognised, thrilled, powerful. To feel anything, really. The sharing part is essential. Unshared art is not art.

Why do we share to make others feel something? Here's where we return to Ernest Becker and man's split between body and ego. Through art, we tell the story of our selves for others to acknowledge. When others feel something at our self-expression, we feel recognised for who we are.

We share to be recognised because recognition gives our lives meaning. While our bodies die when we stop breathing, somewhere deep down we believe we won't really be dead until the last person who knew us also dies.

Whether at the scale of family or history itself, sharing ourselves is the core why of culture. Outward cries for attention from all those egos networks together. Culture is how we don't feel alone in the face of impermanence.

I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all the people that I have met, all the women that I have loved. — Jorge Luis Borges

That makes everyone an artist, really. We all seek recognition in our own ways. The differentiator is scale. Recognition of Da Vinci, Shakespeare, Hitchcock and Kanye West reached epic levels, while it remains intimate for most. Their self-expression objects have claimed large shares of human attention's total addressable market.

Recognition activates mimesis. We reflect someone's self-expression in and with our own self-expression. Attention thus leads replication. You tell friends, write articles, tweet, share photos, post YouTube videos. Another wave of attention-hungry self-expression. On and on it loops:

Remember the word "meme" is derived from mimesis: to mimic, to imitate. Memes fashion culture through copies. Copies can appear as exact clone, something seemingly new and everything in between — but are always product of what came before. Every copy starts (creates) a new cycle. Art are those memes that reflect on culture itself and are created/copied to be shared.

Replication is built-in. A meme integrates:

In first-principle terms, memes are culture and technology in one. Ideas can't spread without technology. To become inter-subjective (culture), the subjective (thoughts) requires copy-function integration. The medium is the meme's replication technology.

Concept and copy-function combine to direct how far the meme travels in culture. It models as an equation:

meme Reach = concept Resonance * medium Replication

There's a third variable: reputation. Who made the meme/art matters. The more resonating memes you create, the more attention every new creation commands. Reputation compounds through proof-of-work.

When The Weeknd was unknown in 2011, music aficionados took years to vibe with his YouTube mixtapes. Today, every track he drops gets millions of listens and shares in the first hours. Inversely, negative reputation builds resistance to the artist's work. Examples abound in this age of cancel culture: Woody Allen, Kevin Spacey, Michael Jackson, Bill Cosby, Joe Rogan — to name a few.

Repeated resonance builds reputation. Once in place, reputation guides resonance and sets the pace for replication:

meme Reach = artist Reputation * (concept Resonance * medium Replication)

Here's a story that makes the point.

Leonardo Da Vinci is an icon of Western culture. Painter, scientist, inventor, engineer, architect — the man embodies Renaissance like no one else.

Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Realise that everything connects to everything else. — Leonardo Da Vinci

Yet, in his time, the average Joe(lle) had never heard of Leonardo. How could they? His science was in notes and drawings, his art in castles and churches. Even in the eyes of the elite with access, it appears Leonardo was overshadowed by Michelangelo and Rafael.

Leonardo's ascent from elusive to icon is best explained through the particular story of one of his most seminal paintings: The Last Supper.

Painted on the walls of Milan's Santa Maria delle Grazie church, The Last Supper's only reached locals. By Leonardo's death in 1519, it had reportedly deteriorated into ruin and seemed destined for anonymity.

Less than a century later, it had become a ubiquitous meme in Europe. For its sheer size and relative absence of optical effects, The Last Supper happened to be a perfect match for copper engraving: printing press-style technology to replicate images. Copies of various versions and sizes pop up all over Europe. The Last Supper becomes the first mass-distributed visual meme in history — a viral .JPEG avant-la-lettre. Leonardo's reputation scaled along, easing resonance for his other work.

This story is not to question Leonardo's creative genius — good luck finding someone more in awe of the man than me — but to demonstrate how technology steers culture.

For attention assets to gain great cultural value, resonance is required. But it's replication that scales.

Faster memes can beat more resonating memes. Fast memes are quick-to-read and quick-to-copy — like the most viral internet memes.

Artists have no choice but to work with the technology available to them. But they can optimise idea expression for maximum scale. That is, to simplify: easy, intuitive and quick to get. Great artists tell monumental stories in a matter of seconds. Instant recognition.

"An intellectual says a simple thing in a hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way." — Charles Bukowski

Simple-to-read, but also simple-to-copy. The Last Supper is iconic because it's both.

By hand, replication of The Last Supper was expensive and slow — no way around it. When engraving emerged, replication skyrocketed because of the way Leonardo coincidentally painted it: simple.

Had Leonardo used more chiaroscuro and sfumato in The Last Supper, other paintings might have been faster to reproduce. Other artists may have caught tailwinds from technology and held in higher regard by culture today. Impossible to know for sure, but consider the scale at which the abundance of The Last Supper copies turned heads to Leonardo's work over others. Human attention is a finite resource and we tend to like what we already know. Coincidence biased Europe to fanboy Leonardo.

Copy-function better predicts cultural impact than concept. Badly communicated ideas are bad ideas.

Time-to-copy is just one of the features of a medium's copy function:

As technology upgrades its features to spread more ideas faster, culture accelerates and complexifies. Let's look at history through the lens of its media.

Pre-speech, memes are stuck in minds and don't spread. Technically, they're not memes at this point, but mere mental models. A mental model only becomes meme when it spreads through material media.

Spoken language is the first media technology. Mental models spread from individual minds into a collective web of minds through sound.

The alphabet ushers in manuscript culture. Memes spread through hand-written language.

The printing press machinises replication. Memes spread through printed language.

Ideas spread via text on paper in the same way, just much faster. Print culture is manuscript culture on steroids.

I don't read a lot of fiction, but I have read every book of A Song Of Ice And Fire — known as Game Of Thrones on screen.

As the name hints, Game Of Thrones explores the struggle for power. In A Clash Of Kings, royal advisor Varys tells Tyrion Lannister a parable:

Varys: “A king, a priest and a rich man sit in a room. Between them stands a common sellsword. Each of the three bids the sellsword to kill the other two. Who lives, who dies?

Tyrion: “Depends on the sell-sword.”

Varys: “Does it? He has neither crown nor gold nor favours with the gods.”

Tyrion: "But he has a sword, the power of life and death.”

Varys: “But if it’s swordsmen who rule, why do we pretend kings hold all the power?"

Varys: "Power resides where men believe it resides. It's a trick. A shadow on the wall. And a very small man can cast a very large shadow."

Power is the ability to produce desired results.

At the individual level, power equals bodily capacity: what you are capable of doing. It ranges from inability to walk to running to being the fastest human on Earth. Technology expands power: it enables the body to do things it otherwise couldn't.

In the social sphere, power is influence over what others do. They behave to your will rather than their own. Parents have power over kids. Employers over employees. Idols over fans. Kings over subjects. States over citizens. Gods over worshippers.

Nature's way to power over others is violence. But violence doesn't scale. By now you know what does scale: stories. Millions of people don't carry out one king's will because they're physically forced to. They do it because they believe that's how it should be. The king's power is a story everyone believes.

To be clear, the story can be about violence. It may tell of the king's strength. His exceptional leadership. Or how he was chosen by God himself.

Whatever the stories, they'll work together to legitimise the ruling cultural order. What's important and what's not. How you should behave and how you shouldn't.

In Part I, we modelled culture as a process of memetic selection. Memes win over minds by being more useful and reproducible than others. Winning memes network together into cultural order. As values, norms and traditions, they dictate how society should organise. Strangers know what to expect from each other. At least, they don't hurt each other. Best case, the sky is the limit for collaboration. The common goals are peace, productivity and prosperity.

Politics encodes the cultural order in laws and institutions that maintain and protect it, with force if necessary. It ensures new memes can't topple established memes with violence (that would be war) but need to win over enough minds with utility and replicability.

That is, in a nutshell, how

The result is hierarchy and hierarchy creates order.

skill barrier

economic barrier

You have power over your body.

power is the measurement of influence you have over things

starting from your own direct environment extending out

Access to copy function: skill, economic, social

A society invested in the democratic meme believes power should reside where elections direct it.

Here's how memes do that: the memes that embed the most accrue cultural caital

Gatekeeper

attention allocation

Burning books and people

Rule the memes, rule the world.

Cashflows = copy right